Hispanic History Month and Lafayette

by Richard Ingram, Chair, Lafayette Alliance

Hispanic History Month is the perfect occasion to recall General Lafayette’s links to Hispanic supporters of the American Revolutionary War and to his support for independence movements in Central and South America.

Few people know the name General Bernardo de Galvez. Galveston is his namesake, as is Saint Bernard Parish, in Louisiana. East Feliciana and West Feliciana Parishes are named after his wife. On December 16, 2014, he became the eighth and last recipient of Honorary United States Citizenship. Congress referred to Galvez as a “hero of the Revolutionary War who risked his life for the freedom of the United States people and provided supplies, intelligence, and strong military support to the war effort.”

Galvez served with the Royal Cantabria, an elite Spanish-French unit, at Pau, France, for three years. It was here he learned to speak French fluently.

He was appointed Governor of Louisiana on January 1, 1777, shortly after King Charles III of Spain decided to covertly support the thirteen British Colonies in their fight for independence. As coincidence would have it Lafayette sailed for America from France four months later.

France and Spain were allies in the French and Indian War (called the Seven Years’ War in Europe); France ceded Louisiana to Spain in 1762, in part to compensate Spain for its loss of Florida to the British. The capital of the Louisiana province was New Orleans.

Galvez proceeded to be very creative in his support. James Willing was an American privateer. He brought captured British vessels into New Orleans. Britain demanded Willing be turned over to them. Galvez refused.

Expeditions to the mid-West by George Rogers Clark to capture Fort Vincennes and secure Ohio were supplied by Galvez. He also put funds at the disposal of patriot Oliver Pollock (originator, interestingly, of the American “$” sign) to help fund campaigns in the mid-West.

On June 21, 1779, in the Treaty of Aranjuez, Spain declared war, officially, on Britain. Galvez now went all out.

On June 25, 1779, British General John Campbell, stationed at Pensacola, received orders from King George III and Lord George Germain to attack New Orleans.

Unknown to Campbell, Galvez had intercepted the letter, and based on its information struck first. Fort Bute (September 7, 1779), Baton Rouge (September 21, 1779), and Natchez, all captured. Six months later, on March 14, 1780, at the Battle of Fort Charlotte, Mobile surrendered.

Lafayette and the Continental Army could not get supplies from harbors on the Atlantic seaboard because of British blockades. Galvez was instrumental in keeping supply lines open by way of southern ports and the Mississippi River. This was critical to the war effort and its importance was underestimated.

In the Siege of Pensacola, March 9-May 8, 1781, Campbell surrendered to Galvez. This effectively ended British threats to cut off southern supply lines to the Continental Army.

General Galvez died of typhus in Mexico City, on November 30, 1786. He was forty years old.

As far as I can tell, Galvez and Lafayette never met. They knew of each other, no doubt, and they were linked by a kindred spirit.

By 1805, Lafayette had settled in as a gentleman farmer at LaGrange, forty miles east of Paris. He followed events in South America closely.

On October 21, 1805, at the Battle of Trafalgar, British Admiral Horatio Nelson, aboard the 100 gun HMS “Victory,” demolished the combined French and Spanish fleets.

Colonies in South America were primed. The press covered ongoing events in North America; it published essays on Enlightenment ideals. The first cry of freedom, El Primer Grito, was in the 1809 Manifesto of the People of Guito (which took its cue from Jefferson): “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary to dissolve the bands which have connected with another…” According to Professor Larrie D. Ferreiro in “Brothers at Arms,” this was translated: “Cuando un pueblo, sea el que fuere, muda el orden de un gobierno establecido largo tiempo.” A domino effect followed with similar declarations in Colombia (1810), Venezuela (1811), and Mexico (1813).

Lafayette supported these movements for independence. He admired the man leading the charge, Simon Bolivar, and referred to him as “the George Washington of Latin America.” Bolivar participated in campaigns for independence in Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, and, of course, Bolivia.

Bolivar’s nephew and adopted son Fernando Bolivar came to the United States in 1822. He attended Germantown Academy, Pennsylvania, and because of his stepfather’s admiration for Thomas Jefferson, the University of Virginia. In July 1825, Lafayette was on his Farewell Tour in America when he visited Germantown. He met Fernando. At the suggestion of George Washington Parke Custis (George Washington was his paternal step-grandfather; Martha Washington his paternal grandmother). Lafayette wrote his ideological counterpart a congratulatory letter on September 1, 1825, and sent with it a pair of pistols owned by Washington, as well as a portrait. Lafayette wrote: “I am happy to think that of all the existing men, and even of all the men of history, General Bolivar is the one to whom my paternal friend would have preferred to offer them [the pistols]. What more can I say to the great citizen whom South America hailed by the name of Liberator, a name confirmed by both worlds, and who, endowed with an influence equal to his disinterestedness, carries in his heart the love of liberty without any exception and the republic without any alloy?”

Bolivar replied on March 20, 1826. “How can I express how much, in my heart, I attach importance to such a testimony of esteem so glorious for me? The family of Mount Vernon honors me beyond my hopes, for the image of Washington, given by the hands of Lafayette, is the most sublime of the rewards that a man can aspire to. Washington was the courageous protector of social reform and you are the citizen hero, the athlete of freedom in America and in the old world.”

On April 13, 2016, at Christie’s Auction House, the pistols sold for $1.8 million. They had been manufactured at Versailles by Napoleon’s personal gunsmith Nicolas-Noel Boutet in 1824, the same year Lafayette launched his Farewell Tour.

Sometimes outcomes hinge on fleeting, little-known moments.

The Battle of Yorktown, in which Lafayette played such a great part, might never have played out as it did. The Continental Army was massively underfunded. It needed cash. Seeing this, French General Rochambeau sent an urgent appeal to Admiral DeGrasse, stationed at the time in the Caribbean, to raise funds for the Yorktown Campaign and for the Continental Army.

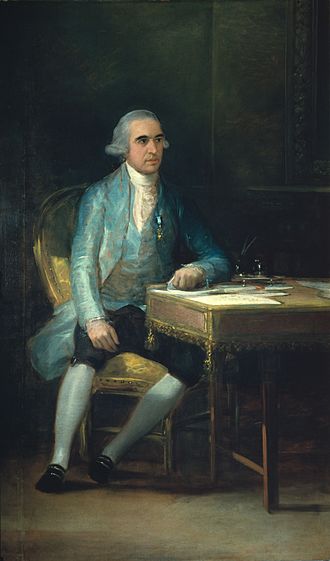

Spanish agent Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, in Havana, Cuba, raised over 500,000 silver pesos in 24 hours. This bankrolled the Siege at Yorktown.

Hispanic History inspires, illuminates, and unites. It is in the Spirit of Lafayette.”

– Richard INgram